- Home

- Sabrina Vourvoulias

Skin in the Game

Skin in the Game Read online

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce, or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

Title Page

Copyright Notice

Begin Reading

Copyright

Geocache

I am at B Street and Somerset, headed for Zombie City. Or La Boca del Diablo—the Devil’s Mouth—as the Latinos in the surrounding barrio call it.

Neither name shows up on GPS, of course, because maps are pure fantasy. What is real doesn’t fit on a grid. And Zombie City/La Boca del Diablo is real.

The zombies, los vivos, the ghosts who live there—all real. Their hunger—real.

It’s the city’s double-named portal to the underworld, and I’m headed there because I have some sympathy for its inhabitants. Because I know hunger. And because it’s my beat.

* * *

Not the Expected Fictions

The zombies are all white.

They take the subway to Somerset, cross the streets of the barrio, then climb through a hole in the railroad fence and scramble down under the Conrail tracks to get their ten dollar fixes of heroin.

After shooting up, while their minds are swaddled in the wooliest moment of their drug, they pace the rails—wordless, aimless, brains on mute—until need turns them back around to do it again.

Los vivos are Latino.

Vivo means alive—as in the mothers, grandmothers, kids, comais, and compais who live on the streets above la Boca del Diablo. But it also means cunning, as in the drug dealers they are always assumed to be, and sometimes are.

The zombies and los vivos coexist for minutes, hours, and sometimes days together: the dead white ones who pay not to see, and the living brown ones who can’t look away.

And around them, flitting in and out of notice, the ghosts. They are black and white and brown, because homelessness may be the only thing in this city that doesn’t heed our segregated neighborhood lines.

The ghosts pitch their tents at the edge of Zombie City and string wards and prayers from tarp to tarp. Better than any other resident or visitor, the ghosts know the truth. No moment of peace is guaranteed.

* * *

Stay In or Take Out

Yolanda looks up at me, hands spread protectively over the bags of food in the trunk of her car. She always parks it at the same spot on the Richmond bridge above Zombie City.

“Ah, Blanca,” she says. It’s not my name, but what she calls me because I take after my father and pass for white. She’s Afrolatina, so the Boricuas and Dominicans call her morena. Or, when they want to slur, prieta.

Spanish is so damned regional, even in the city. As a Mexican from South Philly, morena doesn’t mean black to me, and prieta is an insult more commonly levied at those of us with indigenous heritage. But I learned as soon as I got to the 24th precinct that I’d better adapt to the older barrio’s way.

“Somebody been hassling you, Yoli?” I ask. The ghosts love her because she brings cooked meals for them every other day, but the zombies and dealers can get rough sometimes.

“No, of course not,” she answers, but I see her shoulders relax.

I’m shorter than Yoli—shorter than most women in the United States because my mother is from Chiapas and my tatarabuela was Mam—but I’m big otherwise and all of it is muscle. Plus, I’m quick with my taser and the 9 mm. People know not to mess with Yoli when I’m around.

“La Isleta gave me some pork and yuca for today’s meals,” she says. “And McDonald’s pitched in some fries.” Yoli doesn’t have much to call her own, but she gets every merchant in the barrio to contribute food for the ghosts.

“It’s all still warm. Want some?” she asks. She knows I don’t eat while I’m on duty, but she asks the same thing every time we meet, because she’s got that gene that equates food with caring.

“Nah,” I say, even though my stomach is swimming with Dunkin’ Donuts black and nothing else to soak up its acid. “We got a missing person’s report, I’m just here to look for the kid among the zombies.”

Her nose twitches. If it’s possible for Yoli to feel disdain for another human being—and I’m not sure it is—it’d be for the zombies. It’s not the drug use (she herself carries old scars from addiction), but the fact that most of them have an open future and decent schooling and still choose to live lit.

Despair Yoli understands, boredom not so much. Those are her words. I know it’s not just boredom that drives the zombies, but why argue with her? Yoli is one of the few truly decent people I know, and when I argue I tend to alienate.

“Help me distribute food first,” she says. Her eyes are wide, full of entreaty and the type of pain that makes me want to reconfigure the world.

I raise my eyebrows to let her know I’m on to her. She’s got magic—all of us do—and she’s apt to use it when she’s asking for the ghosts.

She gives a little laugh and lets her eyes slide away from mine. “It is such a pain in the ass that you’re resistant to el embrujo,” she says.

“You know I wouldn’t be here otherwise,” I say.

Long ago I learned that if you reveal one ugly story people will leave off asking for more. They’ll think they’ve gotten to the core of what makes you who you are. Yoli knows that my resistance to magic was born from an act of violence, but she doesn’t know any of the rest. And just as well.

“I’m hearing things from the tents,” Yoli says by way of explanation for her attempted manipulation. “There are new folks in la Boca del Diablo. Almost every ghost I speak to is haunted and in fear and it’s not the usual. I could use your help figuring out what’s going on.”

“Later,” I say. “I have only a short window of opportunity before the missing kid gets caught up and can no longer leave. But if you need help carrying those bags down…”

She shakes her head. I’ve put some ten feet of busted-up asphalt between us before she says anything.

“Jimena.”

Her use of my proper name stops me, spins me around to face her again.

There’s a beat, or two, before she says anything. “Are we caught up? Can either of us really leave?”

“We’re not in thrall to anything,” I say.

She gives me a smile weighted by doubt.

* * *

To Spell It in Spanish, End at I

I think about Yoli’s smile as I climb down the Devil’s Mouth, to the heart of Zombie City. A scan of the tracks is all I need: the zombies cluster under the overpass, busy at their table of floored girder, heating powder on aluminum bowls made from can bottoms before shooting the stuff into their necks, because their arms are already shot to shit.

One look isn’t enough to tell me whether the teen I’m searching for is in any of the tents that wing out from that central hub under the bridge, but it isn’t likely. The ghosts and zombies may share this eight-block stretch of rail bed, but the ghosts are families with children, and they don’t let anyone else near their tarps. Only Yoli.

Still, I do a quick check down the alleys between tents, and plod through a carpet of used syringes as I walk the tracks. Nothing catches my attention. Except a needle almost makes it through the thick sole of my shoe, and I’m thankful—as I am at least once a day—that the department requires

the clunkiest, heaviest mother of a shoe. I would already have the Hep alphabet flowing through my veins if not.

I meet up with Yoli again as she’s hauling her garbage bags full of food down into la Boca and I’m climbing out. “I heard one of the Biblicals mention a new house,” she says when she stops to catch her breath.

The Biblicals are two Boricuas and a Cuban—Ismael, Ezequiel, and Zacarías—who started as lowly bagmen in the eighties and are now kings of whatever makes it onto the barrio streets and down to Zombie City/La Boca del Diablo. Even with their tripled magic, the Biblicals aren’t top echelon in the Philly drug trade. But they’re as close as any Latino has gotten. The fraudulent drug rehabilitation houses they’ve set up to import the already addicted from the island to the mainland has earned them a steady supply of clients and money.

What can I say? We prey best on our own.

* * *

Johnny the Fox

Back up on the streets, there are dozens of people out and about in the commercial hub under the El: Puertorriqueñas and Dominicanas in quilted jackets even though the weather hasn’t turned yet; white girls just off the subway and already crossing onto the lying-est place in the barrio—Hope Street—for party favors to take back to school with them. And, on one of my favorite corners, old men shuffling dominoes on rickety tables in front of the busiest of the old-time bodegas. Their guayaberas are so white they dazzle the eye.

“Eh, Mena,” one of the guayabera clad says to me, overfamiliar as always.

I’ve got more nicknames than I can keep track of, but Officer Villagrán is what I’ve told this guy he should call me. You’ve got to demand your respect when most people are twice your size. But Johnny Zafón is hopeless, and not to be trusted even with a name.

Johnny, el del barrio. Johnny, el Zorro. A charmer, a con man and ex-con. He didn’t serve much time, but enough to bear its marks.

“Know anything about a missing kid?” I ask him. “Five-nine or so, just eighteen, buying for his frat?”

“¿Zombi?”

I nod.

“What will you give me for the information, Jimena, Mena, Menita?” he croons.

Of course. Johnny’s magic is in his voice. Back in Mayagüez, his father used to sing the sailboats safely into port. Even I feel the tug of the rich baritone and his repeating words.

“Nada,” I say. “I don’t buy or sell.”

For an instant his eyes go sad. “You know you’re going to pay sometime.”

“Not today,” I say.

He cocks his head like the fox of his nickname, studies me, then gives me an address. I nod my thanks before turning to go.

“You’re going to need backup,” Johnny says.

* * *

Partners and Other Troubles

Everyone in the barrio hates my partner, Nasey. I don’t blame them. Nasey’s the first to tell you he’s got a thing for spics, likes to fuck them over in every possible sense of the word.

He tried with me when I started, but after that hellish first day I’ve added a pinch of one of my mother’s mixes into every pot of station-house coffee. Nasey always accepts a cup—he says after the childhood he had, he doesn’t ever turn down a gift or free food—and as soon as he has a sip, he becomes nauseated in my presence. Gag reflex on overdrive, acid rushing up his throat, stomach cramps. If he steps away from me, it’s better.

The nausea makes him amenable to breaking protocols, and he drives the cruiser down the streets of our beat in the 24th while I cross the 26th precinct line to work Zombie City/La Boca. Nasey’s got the friendships to make sure the cops at both the 24th and the 26th turn a blind eye to the arrangement. They don’t call it blue solidarity for nothing.

Johnny watches me as all this runs through my head (and across my face), then gives me a glum “are you done with me?” look before ducking into the bodega. No doubt to warn wizened little Tatán Ortíz that the cops will be all over the neighborhood soon, so he should hide any evidence that he trades food and WIC vouchers for cash payouts (minus his cut). They don’t call it barrio solidarity for nothing.

I play with the walkie before I press any buttons. Long enough for the word to spread among los vivos. Long enough for the zombies to hide inside the hollowed-out, trashed couches along the rail bed. Long enough, even, for the ghosts to gather their lives into grocery bags and vacate.

I dally long enough to cost me my badge if someone important were watching.

But that’s the thing: what survives here, good and bad, does so because nobody is watching. Not the council people nor state legislators whose districts overlap in Zombie City; not church do-gooders; not police nor social workers nor public health officials.

Just me.

* * *

Fronts

El Centro de Rehabilitación Corazón Fuerte has a nice façade, but get past the door and its heart is rotten.

The first room we go into has so much trash strewn about it’s impossible to tell whether there’s hardwood or carpet beneath our feet. It was once grand, that I can see from the crumbling plaster detail on the ceiling and the decaying moldings.

There’s no one in the room. Nor in any of the rooms we check on the bottom floor. Nasey says he searched the database as soon as I called, and this rehab is officially listed as serving some twenty-five residents. Whatever money they make from drug sales is frosting on the rip-off-human-services cake.

I find the body on the third floor. Sprawled out, face down, hair dark and wet from some cold sweat she went into before keeling over. It’s not the boy from the missing persons report, but a viva. As we move closer, I see tiny bits of foil kick up and dance in the light streaming through the busted-out window. Addiction’s telltales.

“Another OD,” Nasey says.

I squat down, push the girl’s shoulder to turn her over. Not an OD—her chest is cracked open. It is a disturbingly tidy cavity, without a single organ or even much blood left to pool under it.

“Jesus,” Nasey says. “You ever seen this kind of thing before?”

I shake my head.

Nasey takes a step back, burps, reholsters his gun. “Special Units is going to want a piece of this. Better for us. Except for the part where we have to wait for them to show up.”

Then he burps again. Grimaces. The color climbs up those pale cheeks and I swear it even tints his hair as he fumbles with the radio. “Too much coffee,” he says. His eyes stay on mine longer than they should. Maybe he knows.

Non-Latino folk have magic too. I sense it when I go to the Ukrainian neighborhood to buy pierogies, or when I pick up an order in Chinatown. Sometimes I even feel it reaching out to me from my father’s people if I get roped into working the St. Patrick’s Day parade which, thankfully, isn’t often.

People who talk about code switching don’t know the half of it.

“They’re on their way,” Nasey says. I hear his footsteps as he leaves the room, but my gaze lingers on the dead girl. Her skin is still good, which means she was new to this. I use my thumbs to drag the lids down over her eyes, then shove both thumbs in my mouth.

The taste of her fear-driven flop sweat, her death, washes over my tongue, takes the edge off the hunger that’s always nested inside me. Taste prompts image. I see the girl, face upturned as she waits for her fix, then something striking fast at her chest. Not a knife, but a mouth with scimitar teeth that pop out like double switchblades. I’d like to say I focus on the face of the assailant in the vision, like a good cop would, but I don’t. Just the blood. So much blood. My gut clenches with a sympathetic convulsion.

I take my thumbs out of my mouth and scramble to my feet to find Nasey. He’s leaning against a rickety-looking banister, shooting the shit with two other dudes from the precinct. As soon as he sees me come through the doorway, he steps up to meet me.

“I’ve got to go,” I say. “You’ll have to deal with the paperwork.”

His eyes narrow. “Whadya have?”

“Nothing. A rumor to chec

k out.”

As I start to brush by him, he gags, then swallows hard several times and grabs my arm. “If the rumor looks good, you’ll call me in, right?”

“Sure.”

“I mean it, Villagrán.”

He pronounces my surname perfectly. Nasey may play the part, but he’s not truly a redneck. He’s something else I haven’t been able to decipher yet, hurt and bitter and confident all rolled together.

Because there are so many cops on the fake rehab center call, the streets of el barrio are nearly deserted as I make my way back to the entrance of Zombie City/La Boca. Once more through the packed mud lip, the stone teeth, and down its gullet to the tripas, the innards, of forgotten Philly.

“Tell me about the new ghosts haunting this place,” I say when I find Yoli.

She hands out the ten or so meal boxes in her final garbage bag before she turns to me.

“Not ghosts,” she says. “Monsters.”

* * *

Me, Myself, and Mine

So the thing about monsters is that it is easy to confuse us for human. If we want to we can look the same, smell the same, behave the same.

Some purport we can be identified by our teeth, but they are unreliable indicators at best. A number of us have fangs that fold back and are completely hidden, hinging out only when we get within striking distance of our prey. Others have hollow, venom-stemmed teeth that pivot sideways in their socket joints. These last don’t even have to open their mouths to strike, they wear their concealing smiles the whole time.

But even monsters with fixed rows of fully visible needle teeth don’t need to worry these days. Human kids have started to file their teeth sharp in a bid to be considered edgy and fashionable, and the visual confusion works to the monsters’ advantage.

In any case, nobody has ever been able to see me for what I really am. Not even my mother, who must have started looking for the monstrous telltales the minute I slipped out of her on a slick of vernix and blood. She knew as well—no, better—than any of her foremothers which herbs to use to rid herself of the product of rape, but she didn’t.

So I try to do justice to her faith in me.

Skin in the Game

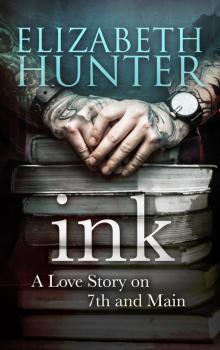

Skin in the Game Ink

Ink